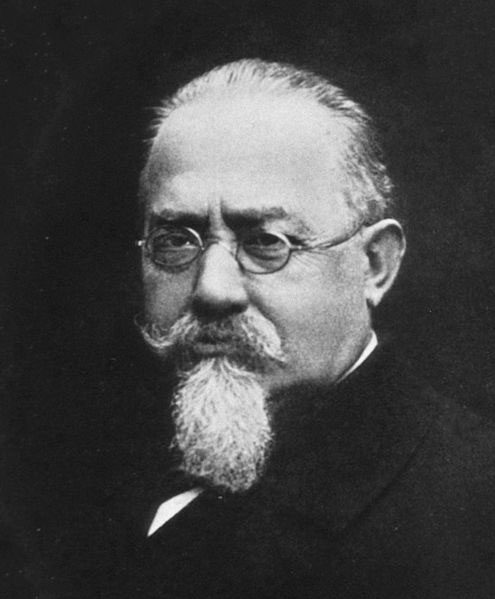

A man creates a museum, and later he becomes a part of that museum himself… on display there at Lombroso Museum in Turin is his own head in a jar. Great psychiatric authority of the nineteenth century, Cesare Lombroso, an Italian who founded the field of criminal anthropology, as it was known.

Lombroso thought criminality was an inherited trait visible in a person’s features, and in an attempt to prove his theory he collected criminals’ remains for analysis. But now some of the descendants of the offenders – whose body parts were taken without permission – want the bones back.

In retrospect, it’s hard not to see the great dangers of their approach. Lombroso’s criminal anthropology sought to isolate the “born criminal” as a deviant type of human being—in fact, criminals were outright evolutionary throwbacks in his thinking. That’s why he studied them not just like a separate culture, but a different species.

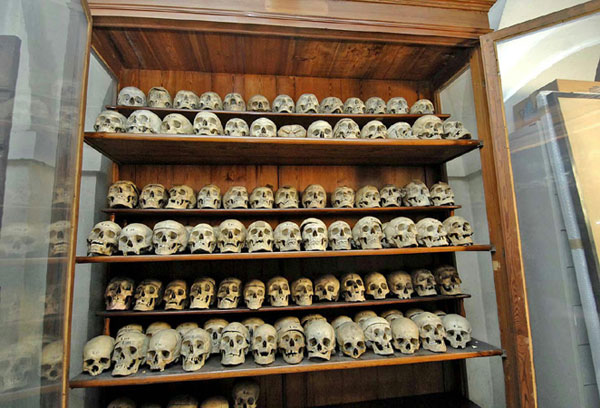

For a positivist like Lombroso, science meant mountains of facts; so he obsessively collected not just statistics, but actual objects and anatomical specimens. He amassed an enormous collection of materials, which he destined for a Museum of Psychiatry and Criminology in his native city of Turin.

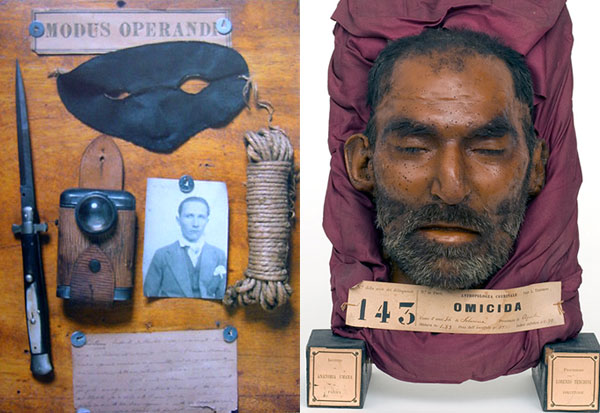

The museum was difficult to access for some years, but recently it reopened in a new location. The collection reveals a maniacal urge to assemble every detail and aspect of criminal life. Besides literal piles of skulls, there are vats of brains, carefully made death masks of murderers, rapists, thieves, and brigands. There are plaster casts of ears showing the degenerate shape characteristic of delinquents and the insane. There are drawings, carvings, poems and songs by criminals, showing their remorseless glory in their evil deeds. There is an impressive collection of prison graffiti, most of it unsuitable for radio. Photos and drawings of prisoners’ tattoos make the argument that criminals are indeed a primitive race; there are even tattooed patches of preserved skin—for every collector knows the value of an original work. And of course, there are murder weapons: daggers, icepicks, cleavers, hatchets, axes, guns, ropes—a whole cornucopia of murder and mayhem.

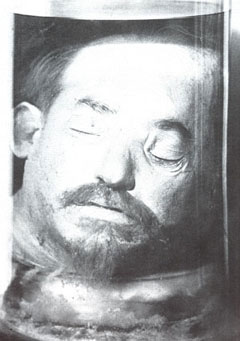

“Wife Killer” says the label beneath a wax-covered head at the Lombroso Museum. “Murderer” says the label under the head to its left.

In Lombroso’s view, the face and the crime were inherently linked: he thought delinquency was physically identifiable through telltale physical features. Lombroso’s ideas were discredited, but his research still remains on display in the Turin museum.

Perhaps every passionate collector yearns to become a part of his collection; Lombroso certainly did. In his will, he left his body to be autopsied by a colleague, so his own skull could be measured and his brain analyzed according to his own theories. His remains were then put in the collection, where still today his whiskered face floats dreamily in a jar.